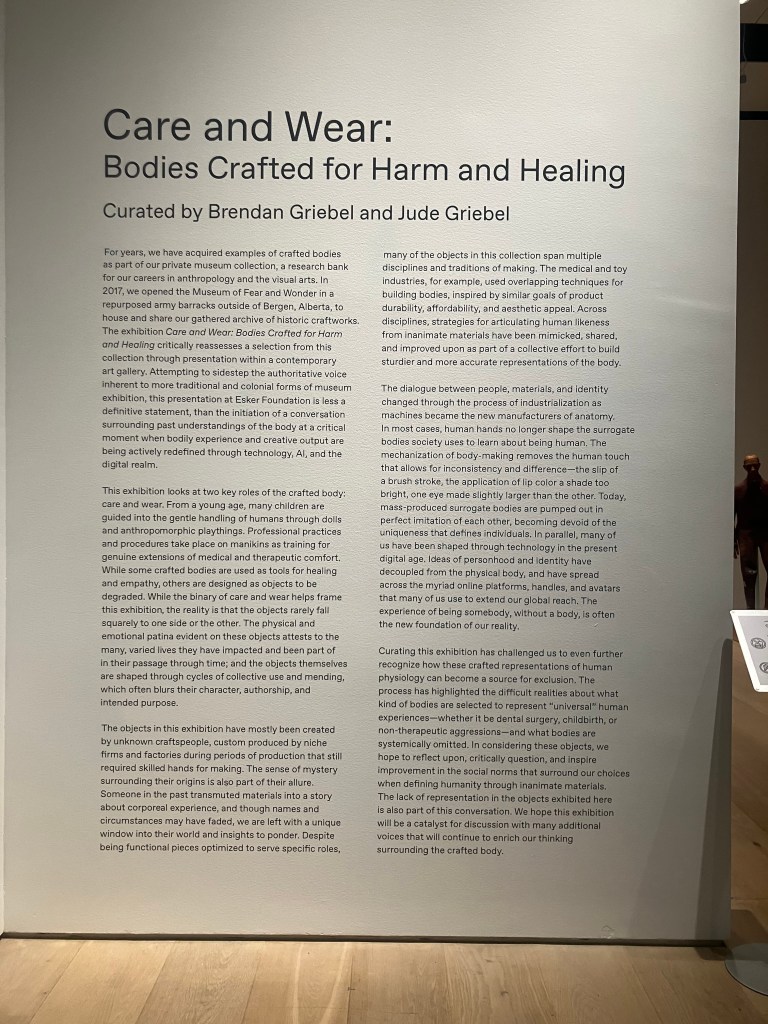

In fall 2023, the Esker Foundation, a non-profit art space in Calgary, Alberta, exhibited dozens of dolls, mannequins, and other representations of human beings from the holdings of the Museum of Fear and Wonder, under the exhibition title Care and Wear: Bodies Crafted for Harm and Healing. The curator statements outline that the figures are made for the most part before the introduction of mass production methods and bear on their bodies the marks of their creation and history.

At the opening, I walked all the way around an obstetric mannequin sitting upright, a Bedford Doll anatomical object, about which the curators recorded an audio segment. She had translucent brown eyelashes, and under the eyelashes, saturated but hazy irises of blue glass. There was no hair on her head, but the scalp was painted tan, shaped to simulate a short hairstyle, although I reacted to the sight as if she had been shaved bald. Her stomach was a cavity open to the air so a medical student could reach inside and manipulate organs which in her current situation were merely a useless tangle of leather at the base of her cavity. I noticed glistening at her throat and leaned in, alarmed, believing for an instant that her head was full of water, and the water was seeping from a seam. I planned to alert a guard or curator. Actually, the substance was clear dried glue that dripped where her head was attached to her neck many decades ago. Surrounded by the busy crowd, I got a strong emotional impression from the mannequin: she was trapped there immobile, there was nothing I could do to help her, we both knew this to be the case; the best I could do was stand together with her for a few moments and give her proper respect. Her hands were amputated at the wrist.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, a burlap rectangle with a headlike protrusion was hung from the ceiling on an X of steel cables, suspended like a masochist on a Saint Andrew’s Cross or an angel in a village nativity play.