- We have to be careful not to adopt theories merely because they give us pleasure. On the other hand, I haven’t figured out how else you would do it.

Setting the altar

The polite academic attempt to introduce the term “New Religious Movement” has largely lost ground in the public sphere. Canadaland Commons, for example, releasing their most recent season on — whatever we’re talking about — chose the punchier and more communicative term: CULTS. When people witness bad behaviour in a spiritual group they want to employ a hard, derogatory word to make their opinions on the behaviour known. This human urge is hard to control. Our desire to communicate our value assessments surely accounts for much of the needless, constant and wonderful expansion in our vocabulary.

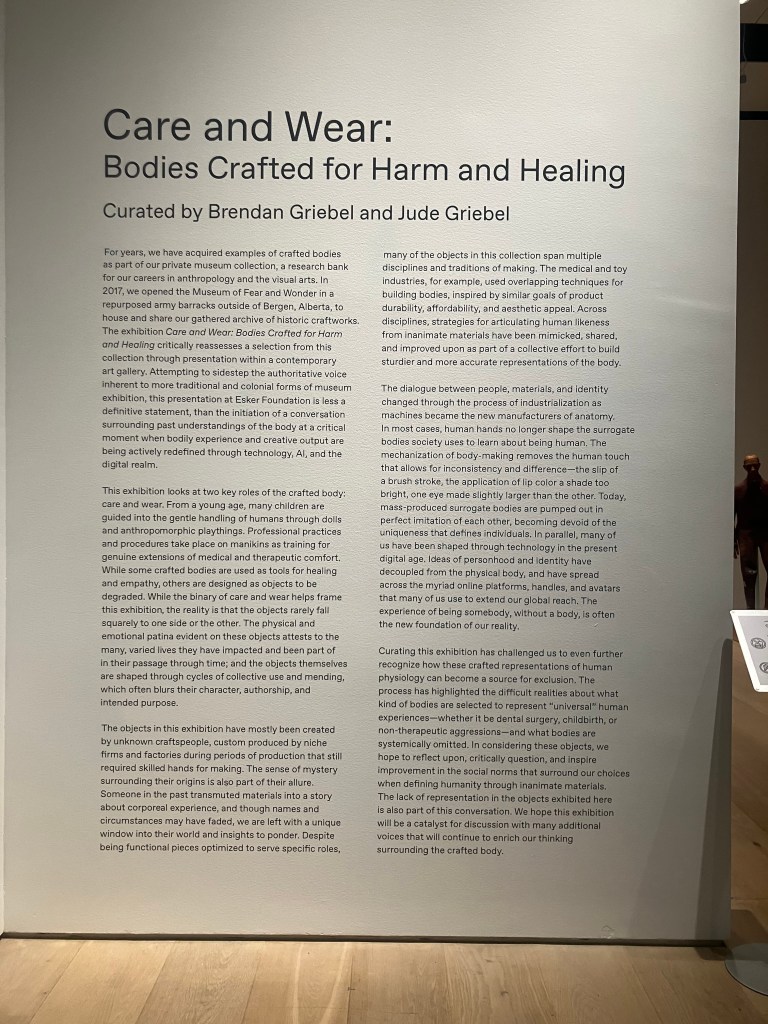

Continue reading “beginning to think about cults”In fall 2023, the Esker Foundation, a non-profit art space in Calgary, Alberta, exhibited dozens of dolls, mannequins, and other representations of human beings from the holdings of the Museum of Fear and Wonder, under the exhibition title Care and Wear: Bodies Crafted for Harm and Healing. The curator statements outline that the figures are made for the most part before the introduction of mass production methods and bear on their bodies the marks of their creation and history.

At the opening, I walked all the way around an obstetric mannequin sitting upright, a Bedford Doll anatomical object, about which the curators recorded an audio segment. She had translucent brown eyelashes, and under the eyelashes, saturated but hazy irises of blue glass. There was no hair on her head, but the scalp was painted tan, shaped to simulate a short hairstyle, although I reacted to the sight as if she had been shaved bald. Her stomach was a cavity open to the air so a medical student could reach inside and manipulate organs which in her current situation were merely a useless tangle of leather at the base of her cavity. I noticed glistening at her throat and leaned in, alarmed, believing for an instant that her head was full of water, and the water was seeping from a seam. I planned to alert a guard or curator. Actually, the substance was clear dried glue that dripped where her head was attached to her neck many decades ago. Surrounded by the busy crowd, I got a strong emotional impression from the mannequin: she was trapped there immobile, there was nothing I could do to help her, we both knew this to be the case; the best I could do was stand together with her for a few moments and give her proper respect. Her hands were amputated at the wrist.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, a burlap rectangle with a headlike protrusion was hung from the ceiling on an X of steel cables, suspended like a masochist on a Saint Andrew’s Cross or an angel in a village nativity play.

No Free Bread

Certainly, no-one in A Little Life has ever eaten at Olive Garden. Although two main characters are meant to come from outside the novel’s affluent New York social scene, both of them are from specific and dramatic types of poverty. One was, famously, raised in a pederastic monastery, followed by almost literally every other setting for sexual abuse of a boy one could imagine (spoilers for A Little Life). The other was raised on a farm by Danish immigrants; we hear few details except for the template one imagines of what it would be like to be raised on a farm by Danish immigrants. Very few rats appear. I am sympathetic to the romance of the rolling yellow prairie bowed under the weight of a Midwestern snow, but something is funny to me about the fact that nobody in this novel ever smoked pot at a fast food job or watched Naruto in a dilapidated farm house while his single father worked the fields for rent.

Well—you can’t get everything in. What I mean perhaps is that nobody in this novel has bad taste, and it feels that the novel couldn’t stand to be otherwise; it would interfere with the premise that all people, including men raised in extremely traumatic circumstances that shatter them at a profound developmental level, are basically, at the centre of their being, upper-class New York art school students.

(I don’t often insert warnings about content, but self-harm and suicide are discussed at length and in considerable emotional detail in the rest of this essay. I never attempted, myself, and am now many years on from consistent or serious suicidality; allow that to influence my credibility as you like.)

Continue reading “masochism and pity”Ring of Keys

Annie Wilkes, fashion icon. She sports pieces like “old brown cowboy boots, blue-jeans with a keyring dangling from one of her belt loops,” and “a man’s tee-shirt now spotted with blood.” Later Stephen King notes that while she sometimes wears frumpy dresses to town, on the days she dons jeans, she leaves her purse behind and sticks her wallet in the jean pocket, “like a man.”

King, who famously writes in an intuitive manner, seems to have slipped at some point in the composition of this manuscript from thinking of Annie Wilkes as a kittens-and-doilies Christian nursy to a big dyke with a Jeep Cherokee. It’s not that granny dress Wilkes and overalls Wilkes couldn’t naturally co-exist in a real woman. I myself have been partial to both at different times; granny dresses, in fact, though I’m sure King didn’t know this, have a certain lesbian cachet of their own. But as far as I can tell Wilkes’s overt mannishness is only introduced later in the text, as if, by natural law, a woman with so much physical power must soon begin wearing a carabiner.

Continue reading “masochism and misery”Pedro Henrique’s debut feature centers on a barely-legal burnout named Miguel. He tumbles through a sequence of nights and days that are loosened from linear time by his habit of partying past sunrise. For company he has a constantly shifting array of friends and friends-of-friends and people-who-hooked-up-with-friends-last-night. (Early on they’re taking poppers at 9am.) He lives with his mom, who we only see conked out on the sofa, maybe drunk. He has a restaurant job but keeps forgetting his shifts and turning up late to beg his co-chef for coke.

Continue reading “thoughts on frágil 2022”The movies are Mona Fastvold’s The World to Come and Alice Wu’s The Half of It. I watched each of them in a very particular state and derived from each a sublime near-religious experience, even though I can’t necessarily defend my experience to anybody on the level of craft. I will try to describe my reasons.

Continue reading “semirational defenses of lesbian movies with sub-7 imdb ratings, a diptych”I don’t like to read Mulholland Drive as a movie about a woman having a dream or something, although I have come to accept that this reading is available. In general, interpretations of anything along these lines don’t interest me — “it’s all a dream” or “it’s all a hallucination” or “it all occurs in the moment before she dies”. These readings pretend to break out of the delusion at the heart of film but actually re-entrench it. That delusion, I mean, being that anything exists in a film.

The dream-or-something twist pretends it’s so clever, and it thinks you’re so stupid. It provokes a flinch of repulsion and offense. The same as when you ask a man at a party about what he’s been watching lately and he says, “Have you ever heard of a little director named David Lynch?”

I don’t like being condescended to about ideas my interlocutor would assume I’d had if he gave me the benefit of thinking I was reasonably clever. This is how it feels to hear, “has it ever occurred to you that part of a movie could be not real?” None of it is real. No movies are real. Movies are a more or less ordered collage of simulated images. Mulholland Drive wants to make us aware of this.

Continue reading “where did you go?”In 2017, I was finishing my undergraduate degree with a project for an XML course where we were directed to digitize a piece of analog media. I discovered that my university had an archive of documents from the women’s movement. Among those documents were several years’ issues of a local lesbian newsletter. I descended to the archive to scan the yellowing documents and stitched together a PDF so that I could transcribe the content. For this task, I used my notebook laptop the size of a day planner, which was cracked from a fall off the hood of my family’s moving car. I sat in the cinema-coffeeshop on campus, or in a bar downtown where a presumed tattoo artist with stretched lobes and a lichenous beard doodled on a napkin beside me.

Continue reading “a story about the post label on a copy of a community newsletter from 1997”Mitski’s new single, “Working for the Knife”, uses the psychic relationship with film to talk about the psychic relationship with art under capitalism. While Mitski is sometimes laundered down to a confessional writer, she often states in interviews that she writes more usually about the process of making music, the process of making art–about which she sings with desperation in Geyser that despite her desires and her best efforts, “it’s not real\ it’s not real\ it’s not real enough.”

In the music video, she acts out a variety of filmic archetypes, from the sinister competence of the chain-smoking cowboy with her invisible cigarette to the manic ecstasy or fear of the tortured female horror movie protagonist, who stomps and flails with her hair flying around her face to expiate whatever enormous terrible emotion it is that lives inside her. (This figure is the “unhinged woman” in the Internet parlance of the moment. Overuse of a word causes what linguists call semantic bleaching, the invisibilization of the embedded metaphor. What comes through the door that sits off its hinges?) What’s terrible about capitalism, she might want to say, is that it commodifies not only the actual product of your creative spirit, but even the very reason you want to create, if you are an artist working in a certain stream. Capitalism causes you to buy and sell your only tool to make life mean anything, to force yourself to manufacture such meaning-making or to fake manufacturing it.

Continue reading “music about movies”