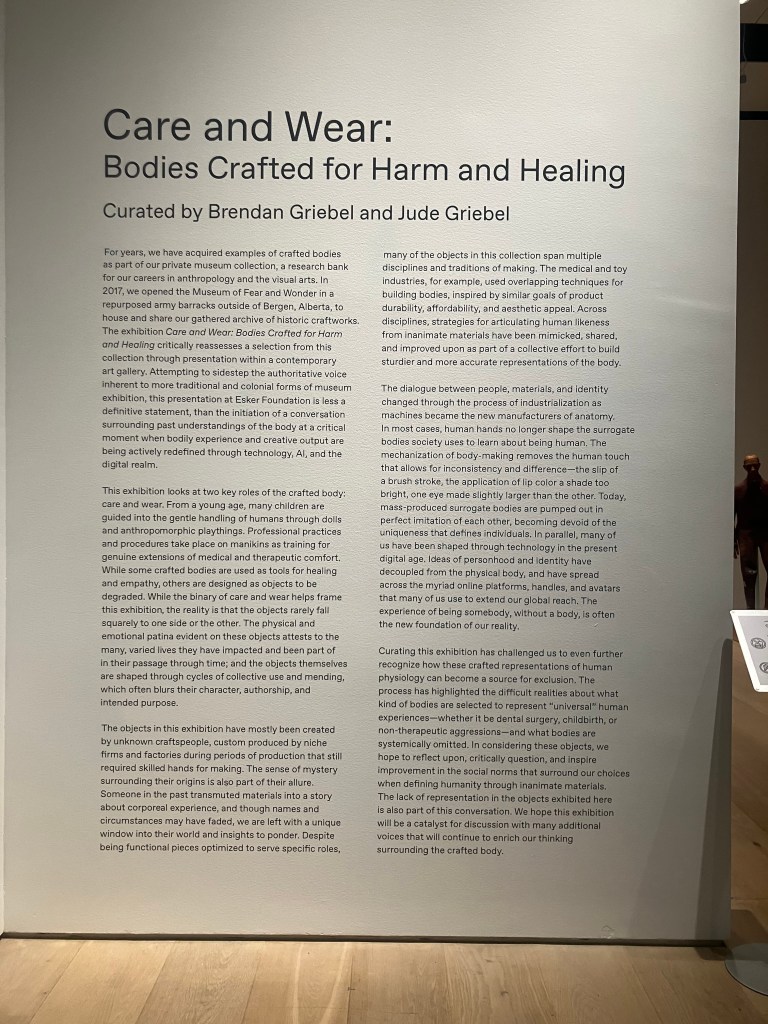

In fall 2023, the Esker Foundation, a non-profit art space in Calgary, Alberta, exhibited dozens of dolls, mannequins, and other representations of human beings from the holdings of the Museum of Fear and Wonder, under the exhibition title Care and Wear: Bodies Crafted for Harm and Healing. The curator statements outline that the figures are made for the most part before the introduction of mass production methods and bear on their bodies the marks of their creation and history.

At the opening, I walked all the way around an obstetric mannequin sitting upright, a Bedford Doll anatomical object, about which the curators recorded an audio segment. She had translucent brown eyelashes, and under the eyelashes, saturated but hazy irises of blue glass. There was no hair on her head, but the scalp was painted tan, shaped to simulate a short hairstyle, although I reacted to the sight as if she had been shaved bald. Her stomach was a cavity open to the air so a medical student could reach inside and manipulate organs which in her current situation were merely a useless tangle of leather at the base of her cavity. I noticed glistening at her throat and leaned in, alarmed, believing for an instant that her head was full of water, and the water was seeping from a seam. I planned to alert a guard or curator. Actually, the substance was clear dried glue that dripped where her head was attached to her neck many decades ago. Surrounded by the busy crowd, I got a strong emotional impression from the mannequin: she was trapped there immobile, there was nothing I could do to help her, we both knew this to be the case; the best I could do was stand together with her for a few moments and give her proper respect. Her hands were amputated at the wrist.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, a burlap rectangle with a headlike protrusion was hung from the ceiling on an X of steel cables, suspended like a masochist on a Saint Andrew’s Cross or an angel in a village nativity play.

When I visited again alone, I walked into the gallery and instantly felt danger and hostility from the mannequins, tempered only by my respectful behaviour. I felt outnumbered. I apologized after taking the photo above, because immediately after lowering my camera I locked eyes with a bust that seemed to deplore me. A group of young people finally arrived to relieve me; I heard someone standing in front of the crash test dummy mock-vomit.

Most art objects in galleries have no history of their own outside the space. They were intended to live in a gallery, or a home like a gallery. They make little sense outside the gallery and would be unhappy there. They are transported and protected with extreme care or assembled on site. They never see the sun, unless through a skylight.

We might say that museum objects brought into a gallery are stripped of their histories; we begin to admire them as sculptures, as shapes and craftworks, like something created for beauty or other effect alone. On the other hand, we might say that museum objects in a gallery are even more centrally defined by their histories than they were in their original context: their histories are what distinguish them from the other objects in other rooms.

It is impossible to look at these figures without imagining them in pain. The effect is of a torture museum or a war memorial in which gruesome pictures are displayed, with appropriate content warnings, for the solemn edification of the visitor. I can’t help but remember a very small photograph, maybe four by six inches, which was stamped into my mind at the Human Rights Museum in Winnipeg: human bodies, at a death camp, in piles. I feel grave in the rooms with the figures. I want to do them each justice and right wrongs done to them which can no longer even be understood. A medical doll obtained by the collectors in Bangkok has gently closed sleeping eyes and an expressive infant’s mouth. The sheer craft of the sculpture is extremely beautiful, the type of stone that looks soft to the touch.

In Travels in Hyperreality, Umberto Eco wrote about the kitsch American wax museums where Leonardo Da Vinci’s “Last Supper” is recreated in life size. The figures of Care and Wear have an effect quite opposite from the uncomfortable, almost repulsive tastelessness of which Eco writes, in the vulgar displays where “everything looks real, and therefore it is real; in any case the fact that it seems real is real.” Paradoxically, in their obvious un-realness these figures have a dignified, morbid animacy. They were clearly never intended to stand in for human beings in any way but the purely functional. They were given exactly the amount of humanity that was required for purpose. Every other effect they acquire is their achievement, or an achievement created between the viewer and the object. As the Museum of Fear and Wonder says: “While some bodies are used as tools for healing, others are designed as objects to be degraded.” The deprivation of their wholeness is literal in some cases: the “phantoms”, medical models with only the requisite parts to practice some technical operation, include an obstretic phantom which is merely thighs and a stomach and a smooth passage between the legs in which a baby doll is complacently lying. The most completely humanlike are the children’s dolls. Even there the exagerrated cuteness of the features only fails to strike us as eerie and fake because of our established cultural conventions of representation of the human face.

The dolls are all sexless. They would have no way to reproduce themselves if they were alive, although some of them, like the gestational dummies I mention above, are technically pregnant or giving birth, and although there are infants. But the actual sites of fertilization and birthgiving are primly ignored by the creators of the figures. The room is sterile. The only force present in the room is death and entropy; there can be no renewal. One bayonet dummy has been stabbed repeatedly between the legs—not where the penis would be on a male opponent, but where the vulva would be on a woman.

The collectors of the objects displayed in the exhibit are brothers, Brendan and Jude Griebel. Brendan is an anthropologist by trade working in the Canadian Arctic. Jude is an sculptor whose original work also draws on the history of representation of the body. Other preoccupations appearing in his work: climate, land; processes of decay, rot, destruction, and weathering; animals.

You could imagine a spectrum of nonhumanness on which animals and mannequins are at perpendicular axes.

Only by perverse ethics, of course, could an object be considered to have the moral authority of an animal. To imply otherwise insults the animal. By Bentham’s classical definition, the object is obviously unable to suffer. Although we are drawn to attribute complex interiority to the mannequin we know that the mannequin cannot experience anything. But the animal and the mannequin share the quality of being like-us and not-like-us along these different axes.

Theorists are interested in animal-human relations partially because of what they tell us about the processes by which dominant groups reduce the human beings they have power over. Dominant groups blinded by their ignorance and egocentrism move the boundary-line between human and animal in ways that are economically and socially convenient for them, to rationalize the maintenance of their tyranny. The boundary line between human and mannequin, too, might be a site of power-struggle. The mannequin reminds us of the corpse. We project that the mannequin may once have had an interiority that has been extinguished so that it now sits posed, inert, and mutilated.

At times the relationship between the corpse and the mannequin is even more charged. Some mannequins are intended to stand in for corpses. The serene face of an elderly white man, complete with the faint discs of the irises under the closed eyelids, would be used by mortuary students to practice cosmetics. The exhibition contains a once-popular model of CPR mannequin named “Rescuci Annie”, or “Anatomical Annie”, explicitly modeled from the face of L’Inconnue de la Seine.

Many artists have used the human-nothuman status of the humanoid sculpture explicitly to explore spaces of abject violence and repulsion. An unnerving aura always hangs over the destroyed body-sculpture. Take, for example, Hans Bellmer’s dismembered mannequins. It is impossible not to suspect that the one who creates these sculpted bodies may harbour sadism that might extend to the real body, the killed body, which the sculpture resembles.

Collecting, obviously, is its own type of fixation. The collector does not necessarily escape whatever moral suspicion we might attribute to an artist of the killed body. Nor is the viewer necessarily exempt. Our obsession with mortal injury and atrocity has conflicting components, even when represented by injuries to an unfeeling object which by any logic cannot experience pain.

This ubiquitous argument that seeing bodies in pain, representations of bodies in pain, satisfies the viewer’s desire to harm others, for any reason, or no reason at all—it seems true in some cases and yet insufficient in others. Torture-horror film, that imaginary of extreme spectacle, is often deplored on this basis, not unfairly. Yet technical close-reading of these torture films often suggests that they orient themselves around identification with the victim as much as, or moreso than, around identification with the torturer. (A 2013 monograph which I find unduly callous overall about the moral weight created by images of atrocity, Steve Jones’ Torture Porn, appears to originate this idea.)

I have heard the theory that we, human beings, developed imaginations to rehearse possible dangers. Then perhaps some of us are drawn to injury, on screen or in the gallery, primarily because we fear being killed. We use the image as a container into which we can pour ourselves and imagine what it would feel like to die, to die terribly, for a bearable moment. We are driven to do this over and over.

Lianne McTavish, in her essay accompanying the exhibition book, “Bodies As Things,” feels motivated to begin her consideration of the exhibit, just as I’ve done here, in a first-person narrative of her interaction with a false body, a CPR dummy she encountered in a first-aid class. Perhaps we both recognize that the profound experience we have with the artificial body is irrational, a little shameful, that we can’t depend reliably on the philosophical you to describe it, that it is imaginary, that it occurs only within the self.

But at least four of us, counting the collectors, experience it. Of my Bedford doll, Jude Griebel says in the audio segment, “You’re seeing this Bedford doll opened up, its body opens, but there’s this happy, pleased expression on its face.” Her teeth are somewhat askew in the mouth, so she gives the impression of having been punched in the face and smiling open-lipped through the blood. “It has these very sensitive details; it has a leather body that’s made to be held and moved. So it is quite vivacious in contrast to a lot of other mannequins before and after, which makes it a very unique object.” Sensitive – perhaps, capable of sensing; vivacious – perhaps, capable of living. He also says of Auzoux échorché models: “They don’t look like dead bodies. They look like something that’s alive and content in its dissected state.” And if these ones are alive and content, others, surely, are alive and in despair.

Visiting the disparate doomed bodies of Care and Wear, I experienced a new way to conceptualize the magnetism of imagined pain: a peculiar moral obligation to witness the injury of these inert figures. This collection provides us the opportunity to attend pointlessly to the maimed object, like mourners filing before the open coffin, or like Antigone, if you like, scattering the dust. In this sense, our fascination testifies to our love for our conspecifics, present and gone, at least as much as it testifies to our voyeurism.